Backfilling Data

Whether new to ClickHouse or responsible for an existing deployment, users will invariably need to backfill tables with historical data. In some cases, this is relatively simple but can become more complex when materialized views need to be populated. This guide documents some processes for this task that users can apply to their use case.

This guide assumes users are already familiar with the concept of Incremental Materialized Views and data loading using table functions such as s3 and gcs. We also recommend users read our guide on optimizing insert performance from object storage, the advice of which can be applied to inserts throughout this guide.

Example dataset

Throughout this guide, we use a PyPI dataset. Each row in this dataset represents a Python package download using a tool such as pip.

For example, the subset covers a single day - 2024-12-17 and is available publicly at https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/. Users can query with:

SELECT count()

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/*.parquet')

┌────count()─┐

│ 2039988137 │ -- 2.04 billion

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 32.726 sec. Processed 2.04 billion rows, 170.05 KB (62.34 million rows/s., 5.20 KB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 239.50 MiB.

The full dataset for this bucket contains over 320 GB of parquet files. In the examples below, we intentionally target subsets using glob patterns.

We assume the user is consuming a stream of this data e.g. from Kafka or object storage, for data after this date. The schema for this data is shown below:

DESCRIBE TABLE s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/*.parquet')

FORMAT PrettyCompactNoEscapesMonoBlock

SETTINGS describe_compact_output = 1

┌─name───────────────┬─type────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ timestamp │ Nullable(DateTime64(6)) │

│ country_code │ Nullable(String) │

│ url │ Nullable(String) │

│ project │ Nullable(String) │

│ file │ Tuple(filename Nullable(String), project Nullable(String), version Nullable(String), type Nullable(String)) │

│ installer │ Tuple(name Nullable(String), version Nullable(String)) │

│ python │ Nullable(String) │

│ implementation │ Tuple(name Nullable(String), version Nullable(String)) │

│ distro │ Tuple(name Nullable(String), version Nullable(String), id Nullable(String), libc Tuple(lib Nullable(String), version Nullable(String))) │

│ system │ Tuple(name Nullable(String), release Nullable(String)) │

│ cpu │ Nullable(String) │

│ openssl_version │ Nullable(String) │

│ setuptools_version │ Nullable(String) │

│ rustc_version │ Nullable(String) │

│ tls_protocol │ Nullable(String) │

│ tls_cipher │ Nullable(String) │

└────────────────────┴─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The full PyPi dataset, consisting of over 1 trillion rows, is available in our public demo environment clickpy.clickhouse.com. For further details on this dataset, including how the demo exploits materialized views for performance and how the data is populated daily, see here.

Backfilling scenarios

Backfilling is typically needed when a stream of data is being consumed from a point in time. This data is being inserted into ClickHouse tables with incremental materialized views, trigging on blocks as they are inserted. These views may be transforming the data prior to insert or computing aggregates and sending results to target tables for later use in downstream applications.

We will attempt to cover the following scenarios:

- Backfilling data with existing data ingestion - New data is being loaded, and historical data needs to be backfilled. This historical data has been identified.

- Adding materialized views to existing tables - New materialized views need to be added to a setup for which historical data has been populated and data is already streaming.

We assume data will be backfilled from object storage. In all cases, we aim to avoid pauses in data insertion.

We recommend backfilling historical data from object storage. Data should be exported to Parquet where possible for optimal read performance and compression (reduced network transfer). A file size of around 150MB is typically preferred, but ClickHouse supports over 70 file formats and is capable of handling files of all sizes.

Using duplicate tables and views

For all of the scenarios, we rely on the concept of "duplicate tables and views". These tables and views represent copies of those used for the live streaming data and allow the backfill to be performed in isolation with an easy means of recovery should failure occur. For example, we have the following main pypi table and materialized view, which computes the number of downloads per Python project:

CREATE TABLE pypi

(

`timestamp` DateTime,

`country_code` LowCardinality(String),

`project` String,

`type` LowCardinality(String),

`installer` LowCardinality(String),

`python_minor` LowCardinality(String),

`system` LowCardinality(String),

`version` String

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (project, timestamp)

CREATE TABLE pypi_downloads

(

`project` String,

`count` Int64

)

ENGINE = SummingMergeTree

ORDER BY project

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_mv TO pypi_downloads

AS SELECT

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi

GROUP BY project

We populate the main table and associated view with a subset of the data:

INSERT INTO pypi SELECT *

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/1734393600-000000000{000..100}.parquet')

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 15.702 sec. Processed 41.23 million rows, 3.94 GB (2.63 million rows/s., 251.01 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 977.49 MiB.

SELECT count() FROM pypi

┌──count()─┐

│ 20612750 │ -- 20.61 million

└──────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.004 sec.

SELECT sum(count)

FROM pypi_downloads

┌─sum(count)─┐

│ 20612750 │ -- 20.61 million

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.006 sec. Processed 96.15 thousand rows, 769.23 KB (16.53 million rows/s., 132.26 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 682.38 KiB.

Suppose we wish to load another subset {101..200}. While we could insert directly into pypi, we can do this backfill in isolation by creating duplicate tables.

Should the backfill fail, we have not impacted our main tables and can simply truncate our duplicate tables and repeat.

To create new copies of these views, we can use the CREATE TABLE AS clause with the suffix _v2:

CREATE TABLE pypi_v2 AS pypi

CREATE TABLE pypi_downloads_v2 AS pypi_downloads

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_mv_v2 TO pypi_downloads_v2

AS SELECT

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi_v2

GROUP BY project

We populate this with our 2nd subset of approximately the same size and confirm the successful load.

INSERT INTO pypi_v2 SELECT *

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/1734393600-000000000{101..200}.parquet')

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 17.545 sec. Processed 40.80 million rows, 3.90 GB (2.33 million rows/s., 222.29 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 991.50 MiB.

SELECT count()

FROM pypi_v2

┌──count()─┐

│ 20400020 │ -- 20.40 million

└──────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.004 sec.

SELECT sum(count)

FROM pypi_downloads_v2

┌─sum(count)─┐

│ 20400020 │ -- 20.40 million

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.006 sec. Processed 95.49 thousand rows, 763.90 KB (14.81 million rows/s., 118.45 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 688.77 KiB.

If we experienced a failure at any point during this second load, we could simply truncate our pypi_v2 and pypi_downloads_v2 and repeat the data load.

With our data load complete, we can move the data from our duplicate tables to the main tables using the ALTER TABLE MOVE PARTITION clause.

ALTER TABLE pypi

(MOVE PARTITION () FROM pypi_v2)

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 1.401 sec.

ALTER TABLE pypi_downloads

(MOVE PARTITION () FROM pypi_downloads_v2)

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.389 sec.

The above MOVE PARTITION call uses the partition name (). This represents the single partition for this table (which isn't partitioned). For tables that are partitioned, users will need to invoke multiple MOVE PARTITION calls - one for each partition. The name of the current partitions can be established from the system.parts table e.g. SELECT DISTINCT partition FROM system.parts WHERE (table = 'pypi_v2').

We can now confirm pypi and pypi_downloads contain the complete data. pypi_downloads_v2 and pypi_v2 can be safely dropped.

SELECT count()

FROM pypi

┌──count()─┐

│ 41012770 │ -- 41.01 million

└──────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec.

SELECT sum(count)

FROM pypi_downloads

┌─sum(count)─┐

│ 41012770 │ -- 41.01 million

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.007 sec. Processed 191.64 thousand rows, 1.53 MB (27.34 million rows/s., 218.74 MB/s.)

SELECT count()

FROM pypi_v2

Importantly, the MOVE PARTITION operation is both lightweight (exploiting hard links) and atomic, i.e. it either fails or succeeds with no intermediate state.

We exploit this process heavily in our backfilling scenarios below.

Notice how this process requires users to choose the size of each insert operation.

Larger inserts i.e. more rows, will mean fewer MOVE PARTITION operations are required. However, this must be balanced against the cost in the event of an insert failure e.g. due to network interruption, to recover. Users can complement this process with batching files to reduce the risk. This can be performed with either range queries e.g. WHERE timestamp BETWEEN 2024-12-17 09:00:00 AND 2024-12-17 10:00:00 or glob patterns. For example,

INSERT INTO pypi_v2 SELECT *

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/1734393600-000000000{101..200}.parquet')

INSERT INTO pypi_v2 SELECT *

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/1734393600-000000000{201..300}.parquet')

INSERT INTO pypi_v2 SELECT *

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/1734393600-000000000{301..400}.parquet')

--continued to all files loaded OR MOVE PARTITION call is performed

ClickPipes uses this approach when loading data from object storage, automatically creating duplicates of the target table and its materialized views and avoiding the need for the user to perform the above steps. By also using multiple worker threads, each handling different subsets (via glob patterns) and with its own duplicate tables, data can be loaded quickly with exactly-once semantics. For those interested, further details can be found in this blog.

Scenario 1: Backfilling data with existing data ingestion

In this scenario, we assume that the data to backfill is not in an isolated bucket and thus filtering is required. Data is already inserting and a timestamp or montonotically increasing column can be identified from which historical data needs to be backfilled.

This process follows the following steps:

- Identify the checkpoint - either a timestamp or column value from which historical data needs to be restored.

- Create duplicates of the main table and target tables for materialized views.

- Create copies of any materialized views pointing to the target tables created in step (2).

- Insert into our duplicate main table created in step (2).

- Move all partitions from the duplicate tables to their original versions. Drop duplicate tables.

For example, in our PyPI data suppose we have data loaded. We can identify the minimum timestamp and, thus, our "checkpoint".

SELECT min(timestamp)

FROM pypi

┌──────min(timestamp)─┐

│ 2024-12-17 09:00:00 │

└─────────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.163 sec. Processed 1.34 billion rows, 5.37 GB (8.24 billion rows/s., 32.96 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 227.84 MiB.

From the above, we know we need to load data prior to 2024-12-17 09:00:00. Using our earlier process, we create duplicate tables and views and load the subset using a filter on the timestamp.

CREATE TABLE pypi_v2 AS pypi

CREATE TABLE pypi_downloads_v2 AS pypi_downloads

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_mv_v2 TO pypi_downloads_v2

AS SELECT project, count() AS count

FROM pypi_v2

GROUP BY project

INSERT INTO pypi_v2 SELECT *

FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/pypi/2024-12-17/1734393600-*.parquet')

WHERE timestamp < '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 500.152 sec. Processed 2.74 billion rows, 364.40 GB (5.47 million rows/s., 728.59 MB/s.)

Filtering on timestamp columns in Parquet can be very efficient. ClickHouse will only read the timestamp column to identify the full data ranges to load, minimizing network traffic. Parquet inndices, such as min-max, can also be exploited by the ClickHouse query engine.

Once this insert is complete, we can move the associated partitions.

ALTER TABLE pypi

(MOVE PARTITION () FROM pypi_v2)

ALTER TABLE pypi_downloads

(MOVE PARTITION () FROM pypi_downloads_v2)

If the historical data is an isolated bucket, the above time filter is not required. If a time or monotonic column is unavailable, isolate your historical data.

ClickHouse Cloud users should use ClickPipes for restoring historical backups if the data can be isolated in its own bucket (and a filter is not required). As well as parallelizing the load with multiple workers, thus reducing the load time, ClickPipes automates the above process - creating duplicate tables for both the main table and materialized views.

Scenario 2: Adding materialized views to existing tables

It is not uncommon for new materialized views to need to be added to a setup for which significant data has been populated and data is being inserted. A timestamp or monotonically increasing column, which can be used to identify a point in the stream, is useful here and avoids pauses in data ingestion. In the examples below, we assume both cases, preferring approaches that avoid pauses in ingestion.

We do not recommend using the POPULATE command for backfilling materialized views for anything other than small datasets where ingest is paused. This operator can miss rows inserted into its source table, with the materialized view created after the populate hash is finished. Furthermore, this populate runs against all data and is vulnerable to interruptions or memory limits on large datasets.

Timestamp or Monotonically increasing column available

In this case, we recommend the new materialized view include a filter that restricts rows to those greater than arbitrary data in the future. The materialized view can subsequently be backfilled from this date using historical data from the main table. The backfilling approach depends on the data's size and the complexity of the associated query.

Our simplest approach involves the following steps:

- Create our materialized view with a filter that only considers rows greater than an arbitrary time in the near future.

- Run an

INSERT INTO SELECTquery which inserts into our materialized view's target table, reading from the source table with the views aggregation query.

This can be further enhanced to target subsets of data in step (2) and/or use a duplicate target table for the materialized view (attach partitions to the original once the insert is complete) for easier recovery after failure.

Consider the following materialized view, which computes the most popular projects per hour.

CREATE TABLE pypi_downloads_per_day

(

`hour` DateTime,

`project` String,

`count` Int64

)

ENGINE = SummingMergeTree

ORDER BY (project, hour)

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_per_day_mv TO pypi_downloads_per_day

AS SELECT

toStartOfHour(timestamp) as hour,

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi

GROUP BY

hour,

project

While we can add the target table, prior to adding the materialized view we modify its SELECT clause to include a filer which only considers rows greater than an arbitary time in the near future - in this case we assume 2024-12-17 09:00:00 is a few minutes in the future.

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_per_day_mv TO pypi_downloads_per_day

AS SELECT

toStartOfHour(timestamp) as hour,

project, count() AS count

FROM pypi WHERE timestamp >= '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

GROUP BY hour, project

Once this view is added, we can backfill all data for the materialized view prior to this data.

The simplest means of doing this is to simply run the query from the materialized view on the main table with a filter that ignores recently added data, inserting the results into our view's target table via an INSERT INTO SELECT. For example, for the above view:

INSERT INTO pypi_downloads_per_day SELECT

toStartOfHour(timestamp) AS hour,

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi

WHERE timestamp < '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

GROUP BY

hour,

project

Ok.

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 2.830 sec. Processed 798.89 million rows, 17.40 GB (282.28 million rows/s., 6.15 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 543.71 MiB.

In the above example our target table is a SummingMergeTree. In this case we can simply use our original aggregation query. For more complex usecases which exploit the AggregatingMergeTree, users will use -State functions for the aggregates. An example of this can be found here.

In our case, this is a relatively lightweight aggregation that completes in under 3s and uses less than 600MiB of memory. For more complex or longer-running aggregations, users can make this process more resilient by using the earlier duplicate table approach i.e. create a shadow target table, e.g., pypi_downloads_per_day_v2, insert into this, and attach its resulting partitions to pypi_downloads_per_day.

Often materialized view's query can be more complex (not uncommon as otherwise users wouldn't use a view!) and consume resources. In rarer cases, the resources for the query are beyond that of the server. This highlights one of the advanages of ClickHouse materialized views - they are incremental and don't process the entire dataset in one go!

In this case, users have several options:

- Modify your query to backfill ranges e.g.

WHERE timestamp BETWEEN 2024-12-17 08:00:00 AND 2024-12-17 09:00:00,WHERE timestamp BETWEEN 2024-12-17 07:00:00 AND 2024-12-17 08:00:00etc. - Use a Null table engine to fill the materialized view. This replicates the typical incremental population of a materialized view, executing it's query over blocks of data (of configurable size).

(1) represents the simplest approach is often sufficient. We do not include examples for brevity.

We explore (2) further below.

Using a Null table engine for filling materialized views

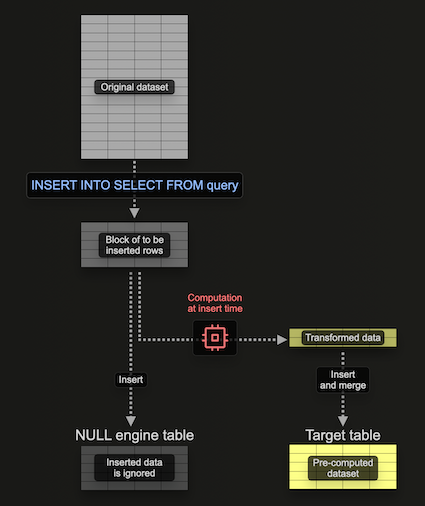

The Null table engine provides a storage engine which doesn't persist data (think of it as the /dev/null of the table engine world). While this seems contradictory, materialized views will still execute on data inserted into this table engine. This allows materialized views to be constructed without persisting the original data - avoiding I/O and the associated storage.

Importantly, any materialized views attached to the table engine still execute over blocks of data as its inserted - sending their results to a target table. These blocks are of a configurable size. While larger blocks can potentially be more efficient (and faster to process), they consume more resources (principally memory). Use of this table engine means we can build our materialized view incrementally i.e. a block at a time, avoiding the need to hold the entire aggregation in memory.

Consider the following example:

CREATE TABLE pypi_v2

(

`timestamp` DateTime,

`project` String

)

ENGINE = Null

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_per_day_mv_v2 TO pypi_downloads_per_day

AS SELECT

toStartOfHour(timestamp) as hour,

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi_v2

GROUP BY

hour,

project

Here, we create a Null table, pypi_v2, to receive the rows that will be used to build our materialized view. Note how we limit the schema to only the columns we need. Our materialized view performs an aggregation over rows inserted into this table (one block at a time), sending the results to our target table, pypi_downloads_per_day.

::note

We have used pypi_downloads_per_day as our target table here. For additional resiliency, users could create a duplicate table, pypi_downloads_per_day_v2, and use this as the target table of the view, as shown in previous examples. On completion of the insert, partitions in pypi_downloads_per_day_v2 could, in turn, be moved to pypi_downloads_per_day. This would allow recovery in the case our insert fails due to memory issues or server interruptions i.e. we just truncate pypi_downloads_per_day_v2, tune settings, and retry.

:::

To populate this materialized view, we simply insert the relevant data to backfill into pypi_v2 from pypi.

INSERT INTO pypi_v2 SELECT timestamp, project FROM pypi WHERE timestamp < '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 27.325 sec. Processed 1.50 billion rows, 33.48 GB (54.73 million rows/s., 1.23 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 639.47 MiB.

Notice our memory usage here is 639.47 MiB.

Tuning performance & resources

Several factors will determine the performance and resources used in the above scenario. We recommend readers understand insert mechanics documented in detail here prior to attempting to tune. In summary:

- Read Parallelism - The number of threads used to read. Controlled through

max_threads. In ClickHouse Cloud this is determined by the instance size with it defaulting to the number of vCPUs. Increasing this value may improve read performance at the expense of greater memory usage. - Insert Parallelism - The number of insert threads used to insert. Controlled through

max_insert_threads. In ClickHouse Cloud this is determined by the instance size (between 2 and 4) and is set to 1 in OSS. Increasing this value may improve performance at the expense of greater memory usage. - Insert Block Size - data is processed in a loop where it is pulled, parsed, and formed into in-memory insert blocks based on the partitioning key. These blocks are sorted, optimized, compressed, and written to storage as new data parts. The size of the insert block, controlled by settings

min_insert_block_size_rowsandmin_insert_block_size_bytes(uncompressed), impacts memory usage and disk I/O. Larger blocks use more memory but create fewer parts, reducing I/O and background merges. These settings represent minimum thresholds (whichever is reached first triggers a flush). - Materialized view block size - As well as the above mechanics for the main insert, prior to insertion into materialized views, blocks are also squashed for more efficient processing. The size of these blocks is determined by the settings

min_insert_block_size_bytes_for_materialized_viewsandmin_insert_block_size_rows_for_materialized_views. Larger blocks allow more efficient processing at the expense of greater memory usage. By default, these settings revert to the values of the source table settingsmin_insert_block_size_rowsandmin_insert_block_size_bytes, respectively.

For improving performance, users can follow the guidelines outlined here. It should not be neccessary to also modify min_insert_block_size_bytes_for_materialized_views and min_insert_block_size_rows_for_materialized_views to improve performance in most cases. If these are modified, use the same best practices as discussed for min_insert_block_size_rows and min_insert_block_size_bytes.

To minimize memory, users may wish to experiment with these settings. This will invariably lower performance. Using the earlier query, we show examples below.

Lowering max_insert_threads to 1 reduces our memory overhead.

INSERT INTO pypi_v2

SELECT

timestamp,

project

FROM pypi

WHERE timestamp < '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

SETTINGS max_insert_threads = 1

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 27.752 sec. Processed 1.50 billion rows, 33.48 GB (53.89 million rows/s., 1.21 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 506.78 MiB.

We can lower memory further by reducing our max_threads setting to 1.

INSERT INTO pypi_v2

SELECT timestamp, project

FROM pypi

WHERE timestamp < '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

SETTINGS max_insert_threads = 1, max_threads = 1

Ok.

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 43.907 sec. Processed 1.50 billion rows, 33.48 GB (34.06 million rows/s., 762.54 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 272.53 MiB.

Finally, we can reduce memory further by setting min_insert_block_size_rows to 0 (disables it as a deciding factor on block size) and min_insert_block_size_bytes to 10485760 (10MiB).

INSERT INTO pypi_v2

SELECT

timestamp,

project

FROM pypi

WHERE timestamp < '2024-12-17 09:00:00'

SETTINGS max_insert_threads = 1, max_threads = 1, min_insert_block_size_rows = 0, min_insert_block_size_bytes = 10485760

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 43.293 sec. Processed 1.50 billion rows, 33.48 GB (34.54 million rows/s., 773.36 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 218.64 MiB.

Finally, be aware that lowering block sizes produces more parts and causes greater merge pressure. As discussed here, these settings should be changed cautiously.

No timestamp or monotonically increasing column

The above processes rely on the user have a timestamp or monotonically increasing column. In some cases this is simply not available. In this case, we recommend the following process, which exploits many of the steps outlined previously but requires users to pause ingest.

- Pause inserts into your main table.

- Create a duplicate of your main target table using the

CREATE ASsyntax. - Attach partitions from the original target table to the duplicate using

ALTER TABLE ATTACH. Note: This attach operation is different than the earlier used move. While relying on hard links, the data in the original table is preserved. - Create new materialized views.

- Restart inserts. Note: Inserts will only update the target table, and not the duplicate, which will reference only the original data.

- Backfill the materialized view, applying the same process used above for data with timestamps, using the duplicate table as the source.

Consider the following example using PyPi and our previous new materialized view pypi_downloads_per_day (we'll assume we can't use the timestamp):

SELECT count() FROM pypi

┌────count()─┐

│ 2039988137 │ -- 2.04 billion

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec.

-- (1) Pause inserts

-- (2) Create a duplicate of our target table

CREATE TABLE pypi_v2 AS pypi

SELECT count() FROM pypi_v2

┌────count()─┐

│ 2039988137 │ -- 2.04 billion

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.004 sec.

-- (3) Attach partitions from the original target table to the duplicate.

ALTER TABLE pypi_v2

(ATTACH PARTITION tuple() FROM pypi)

-- (4) Create our new materialized views

CREATE TABLE pypi_downloads_per_day

(

`hour` DateTime,

`project` String,

`count` Int64

)

ENGINE = SummingMergeTree

ORDER BY (project, hour)

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW pypi_downloads_per_day_mv TO pypi_downloads_per_day

AS SELECT

toStartOfHour(timestamp) as hour,

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi

GROUP BY

hour,

project

-- (4) Restart inserts. We replicate here by inserting a single row.

INSERT INTO pypi SELECT *

FROM pypi

LIMIT 1

SELECT count() FROM pypi

┌────count()─┐

│ 2039988138 │ -- 2.04 billion

└────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec.

-- notice how pypi_v2 contains same number of rows as before

SELECT count() FROM pypi_v2

┌────count()─┐

│ 2039988137 │ -- 2.04 billion

└────────────┘

-- (5) Backfill the view using the backup pypi_v2

INSERT INTO pypi_downloads_per_day SELECT

toStartOfHour(timestamp) as hour,

project,

count() AS count

FROM pypi_v2

GROUP BY

hour,

project

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 3.719 sec. Processed 2.04 billion rows, 47.15 GB (548.57 million rows/s., 12.68 GB/s.)

DROP TABLE pypi_v2;

In the penultimate step we backfill pypi_downloads_per_day using our simple INSERT INTO SELECT approach described earlier. This can also be enhanced using the Null table approach documented above, with the optional use of a duplicate table for more resiliency.

While this operation does require inserts to be paused, the intermediate operations can typically be completed quickly - minimizing any data interruption.